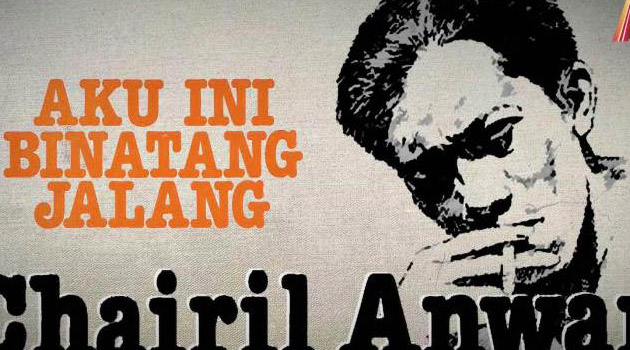

Rebel With a Cause: How Chairil Anwar’s Disgust for Establishment Takes Indonesian Poetry to Next Level

(“Here I am, a wild beast”) is the most famous line by arguably Indonesia’s most famous poet of all time, Chairil Anwar. The line seems to perfectly embody the rebellious spirit of the poet who, according to many critics, modernized and changed the course of Indonesian poetry during the heady days of the Indonesian Revolution in the late 1940s.

Chairil’s first clarion call was his haranguing of his more conservative forebears in Pujangga Baru, a literary magazine founded in 1933 by Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana, Armijn Pane and Amir Hamzah – the three giants of modern Indonesian literature.

Pujangga Baru was more than a magazine, it was the progenitor of a literary movement to modernize Indonesian literature by drawing new inspirations from the West.

The group’s founders had wanted to form a club for like-minded nationalist intellectuals, but it soon became an elitist clique.

In a discussion held at Jakarta’s Komunitas Salihara on Wednesday (02/05), poet Hasan Aspahani – who released his fictionalized biography of Chairil last year – said the modernist hero insulted Pujangga Baru poets for not being avant-garde enough, and for letting themselves be “trapped in mediocrity.”

According to Hasan, in one of his many postcards to critic H. B. Jassin, Chairil had called the Pujangga Baru poets “copycats of ’80s poets [a reference to De Tachtigers or the [Eighteen] Eighties poets in the Netherlands]… directionless copycats.”

Chairil wrote his famous j’accuse against Pujangga Baru, “Hoppla!” in the first issue of Pembangunan magazine in 1945.

In it, the poet excoriated the Pujangga Baru school for failing to bring any new development to Indonesian poetry.

#ChairilReads

Chairil was an avid reader who, legend has it, was not above stealing books from shops and libraries around where he lived in Cikini, Central Jakarta.

The poet was a MULO (Dutch junior high school) dropout, but he was fluent in three languages, Indonesian, English and Dutch.

Chairil spent several years living with his uncle Sutan Sjahrir when he first moved to Batavia (now Jakarta) from his hometown of Medan in North Sumatra.

Sjahrir was an intellectual who later became the first prime minister of Indonesia in 1945. He had a large library at his house that Chairil helped himself to anytime he wanted.

According to Hasan, Sjahrir said in an article in Pujangga Baru that he kept books by James Joyce, Franz Kafka, D.H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway and Aldous Huxley in his library.

In his book on Chairil, “Chairil Anwar – Pelopor Angkatan 45” (“Chairil Anwar – Icon of the 1945 School of Poets”), Jassin, also a close friend of Chairil’s, said the poet had always read widely.

Chairil’s favorite poets included modernist greats Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot as well as Auden, Aiken, Rilke and Lorca.

He also looked up to Dutch poets J.J. Slauerhoff, Edy Du Perron, Menno Ter Braak and Hendrik Marsman.

Jassin mentioned in one of his letters that Chairil often borrowed “weighty” books from him, including titles by political activist Henriette Rolland Holst and historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga.

Hasan said changes in Chairil’s poetry can be traced back to his reading habits.

In the beginning of his career, Chairil was heavily influenced by Marsman, Perron and Slauerhoff, but by the end he was showing strong influences from Auden, Conrford and Rilke.

Just before he died in 1949, Chairil had been trying to write longer free verse poems.

Some that have seen the light of day include “Slama Bulan Menyinari Dadanya” (“As Long as the Moon Shines on His Chest”) and “Aku Berkisar Di Antara Mereka” (“I Walk Among the Crowd”).

Out With the Old, In With the New

Poet and critic Zen Hae, who shared the Salihara stage with Hasan, said one important aspect of Chairil’s revolutionary poetry was his use of colloquial, everyday language.

Zen claimed Chairil was influenced by Melayu Pasar (Market Malay) often used by Peranakan (Chinese-Indonesian) authors of popular romance novels.

Chairil’s liberal use of everyday language was a big middle finger raised in the face of Pujangga Baru poets.

“Pujangga Baru thought Melayu Pasar was too embarrassing to be used in serious literature. They were very high-brow. Chairil’s sympathies were more with low-brow writers like the Peranakans,” Zen said.

Chairil also likes to play with the syntax of the Indonesian language, inverting his phrases and clauses, and sometimes chopping up his words into unfamiliar forms.

But even though Chairil mostly wrote free verses, traces of traditional Malay poetic form like the pantun can be easily found in his poetry, as Sylvia Tiwon pointed out in her 1992 essay, “Ordinary Songs: Chairil Anwar and Traditional Poetics.”

This is not so surprising since Chairil grew up in Medan, North Sumatra, and spoke the local Deli Malay dialect.

“Senja di Pelabuhan Kecil” (“Sunset at a Small Port”) is a perfect example. It shows Chairil’s flair for unconventional, intense language that creates “news that stays fresh,” but at the same time the poem has a fixed rhyming scheme and a vaguely pantun-esque structure.

Rebel With a Cause

Chairil wasn’t without his critics. As Zen pointed out, in the magazine Pandji Pustaka Jassin had criticized Chairil and his peers for not having entirely moved on from the romantic traditions.

In Mimbar Indonesia, another critic Asrul Sani said that poetry from Chairil’s era was often too “full of emotions.”

In his article, Asrul quoted Eliot’s proclamation from his famous essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” that “poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion.”

Nirwan Dewanto, a poet and critic who was also at the Salihara discussion, claimed that Chairil’s lines are often pseudo-philosophical – more aphoristic than truly thought-provoking.

Nevertheless, Zen said Chairil’s “refusal to succumb to dictionary and grammar” had taken his – and Indonesian – poetry to a new level, creating a new style of intense lyrical poetry whose influences are still felt to this day.

“And isn’t that the raison d’être of every poet? If we can’t create something new, why bother becoming a poet?” Zen said.

Courtesy : JakartaGlobe

Photo :wordpress.com

[social_warfare buttons=”Facebook,Pinterest,LinkedIn,Twitter,Total”]